Few oil-rich economies have as ambitious plans for economic diversification as those of the GCC. The Gulf monarchies do bring along many assets in their quest for post-oil growth: fairly mature bureaucracies, good infrastructure and solid public goods provision. They rank higher in all of these regards than most other hydrocarbons producers outside of the OECD. And yet, the GCC also faces some obstacles to economic diversification that are unique to the region and not always well understood by policy-makers or their advisors.

Most notably, the unusually generous unique social contract that provides for GCC citizens creates cost structures for private producers and disincentives on the private labour market that make conventional industrialisation strategies difficult to implement. There is no clear blueprint or precedent for overcoming these constraints. Diversification will instead require cautious experimentation and a gradual reformulation of the social contract in a way that reduces distortions while maintaining living standards for GCC nationals.

How State Generosity has Increased the Costs of Production

GCC governments have been successful in spreading middle-class wealth fairly broadly among national populations that, by and large, were desperately poor just two generations ago. Yet the spreading of wealth through channels like generous state employment have also created fairly high costs for local producers: Like in other high-income countries, operating businesses in the GCC is not cheap, especially when firms are under pressure to employ nationals whose expectations on wages and working hours are informed by the generous packages available in government.

Different from conventional high-income countries, however, productivity levels in GCC private sectors have not kept pace with the rapid improvement in living standards and wages for citizens. This means that there is a real disconnect between costs of production and efficiency of production. That does not affect the fortunes of the non-tradables sector in the GCC very much, but it impedes the competitiveness of the tradables sector outside of oil and hydrocarbons-related products. A conventional industrialisation path based on relatively low technology levels but cheap labour – which, as Dani Rodrik has shown, has become difficult under the best of circumstances – is not open to the GCC. Even foreign workers, who on average are paid a fraction of citizens in the private sector, are considerably more expensive to employ in the GCC than in their countries of origin.

The relative weakness of national human resources is at the crux of the problem. GCC labour markets continue to be deeply distorted by expansive government employment, which accounts for about 70 percent of all jobs held by GCC citizens. It undermines entrepreneurial incentives, raises wage expectations, and weakens the motivation to acquire skills relevant for the private sector. While this set-up provides middle class lifestyle for a large share of nationals, the resulting labour market structures stymie private-driven diversification.

Different from non-oil economies, citizen wages in GCC economies tend to lie significantly above their marginal product, as evidenced by a striking scatterplot contained in a recent IMF Article IV report on Saudi Arabia (see p. 22). As productivity and practical skills remain relatively weak, the political pressure to provide more state employment in turn remains strong. At the same time, firms tend to focus on the non-tradables sector serving the local market, where they can rely on state-generated demand and can afford to incur higher production costs.

The GCC economies are a victim of their own success: unlike some oil-rich kleptocracies outside of the region, they have shared their riches relatively widely and greatly improved national living standards. As a result, however, production costs and real exchange rates are high, while productivity has been flatlining.

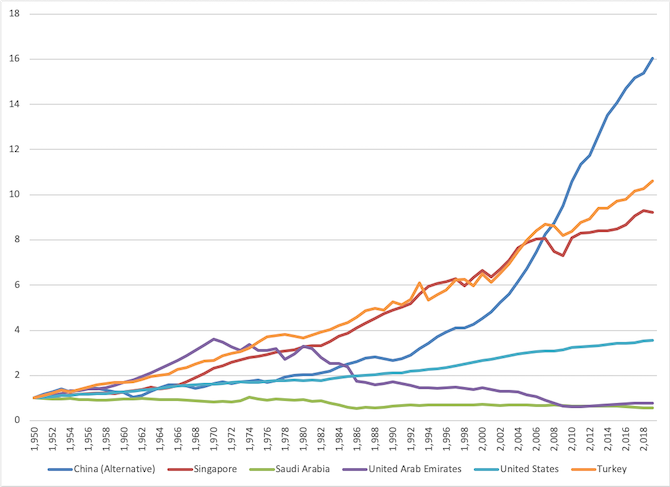

Source: Conference Boards

As competing on the cost of labour inputs is not feasible, the GCC can only become internationally competitive by leapfrogging into advanced kinds of production. But this is difficult and few economies have managed to do so. Dubai has accomplished some of it through heavy use of skilled foreign manpower in its advanced service sectors, but the model is unlikely to be replicable for GCC countries with larger national populations. The experience of populous commodity-rich countries outside of the region, like the oft-cited Malaysian case, is not particularly relevant. Different from the GCC, Malaysia was not a rich, middle class-based society before industrialisation. Its per capita rents were limited and it could therefore leverage ample cheap labour in the first stages of industrial growth.

That said, GCC economies have assets that other late industrialisers do not: ample capital, high penetration of consumer technology, well-run state-owned enterprises in critical sectors, and a geostrategic position between Europe, Asia and Africa. Some economists see access to relatively cheap foreign labour as a further advantage, but the long-term evidence seems to be that reliance on such labour has pushed GCC economies onto a low productivity path – unlike other industrialisers, where growing supply constraints on national labour pushed firms into investing into skills and technology. GCC economies by and large remain organised around foreign labour – cheap enough to maintain a convenient service economy for citizens but not cheap enough to compete with truly low-cost producers in Asia.

Is There a Solution?

The first conclusion from the above discussion has to be that there is no ready blueprint for GCC diversification: both the assets and the constraints of GCC economies are rather unique. The best that policy-makers can do is to alleviate the constraints in a target fashion while facilitating wide-ranging experimentation with new models of production that might leverage the GCC’s specific assets.

The key binding constraint is low labour productivity. While this can be said about almost every economy struggling to diversify, the factors depressing productivity of national labour in the region are rather specific. They include a labour market that is organised around public sector employment, in which nationals are deterred from seeking private sector jobs through competition with low-cost foreign workers, and in which employers have few incentives to invest in skills or technology given their barely constrained ability to import labour. All these incentives need to change. This could be through gradually converting excess public sector employment into a much less distortionary general cash grant for all citizens, subsidies for national labour in the private market (as already implemented in Kuwait) or migration management that decreases incentives to rely on low-cost workers. We do not know the ideal policy mix, but we know which distortions need tackling, while recognising the political need to maintain a middle-class lifestyle for citizens.

Local experience shows that labour market attitudes can change. In some hotels in Riyadh, Saudis now provide room service – something that was socially unthinkable a decade ago. The willingness to take on private sector work is increasing. This needs to be accompanied by more targeted efforts at upskilling, moving away from the over-production of university graduates in subjects of limited practical relevance. Saudi Arabia’s university enrolment rate of around 70 percent might be the highest in the world, but few programmes prepare graduates for the actual labour market – many of them instead merely serve to postpone unemployment by a few years, while increasing expectations of white-collar employment.

There is time to redefine the social contract in the majority of GCC countries: with the exception of Bahrain and Oman, they retain enough fiscal runway to smooth the transition to a new system. But under current oil prices, this will not be the case much longer, especially in the relatively less wealthy Saudi Arabia. Sticking to the current welfare system for too long increases the risk of a forced adjustment in which the social contract is forcibly dismantled through fiscal and currency crises – not unlike what Egypt experienced in recent years.

Even if the incentive environment is reformed, the GCC’s unique development constraints mean that there is no cookie-cutter recipe for diversification and the international benchmarking that the region’s public policy consultants are so fond of often is of limited relevance. The GCC instead has to find its own path towards leveraging its strengths in digital literacy, heavy industry, infrastructure, geography and consumer tastes. Doing this will require a wide range of experimentation with new forms of production, a process of discovery that can be supported through provision of credit, equity, targeted training and specialised infrastructure. The process should involve private capital and be decentralised. It is less advisable to focus on a few large, state-engineered bets that could go wrong and end up as white elephants.

Until now, none of the GCC governments have really touched the core distributional bargain based on public employment. While there is much investment in new sectors and infrastructures, the policy discussion about sustainability and reform of the GCC social contract remains limited. It is the hardest bit of the economic reform process, but also the one that will pay the strongest long-term dividends.